Industry still behind in race for enough truck parking spaces

- No Comments

03 Nov

Trying to address the nationwide truck parking shortage is akin to the slowest runner in a race trying to catch up to the fastest. Finding adequate parking is a problem that continues to vex the trucking industry in much the same way.

Efforts at solutions to the shortage have been compounded by additional headwinds such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, a shortfall of drivers that has ballooned to 80,000, the current supply chain crisis clogging ports and freight lanes, and infrastructure in the U.S. that is decaying to the point where operations are profoundly affected.

A frequent ad-hoc solution for drivers is parking on highway entrance and exit ramps. In most states, this practice is illegal and puts drivers at risk.

In the landmark 2015 Jason’s Law Survey by the Federal Highway Administration, 37 state DOTs reported problems with truck parking, notably in congested freight corridors in the Northeast, in the Mid-Atlantic, and up and down the East Coast, but also out west in California’s freight lanes and the Pacific Northwest.

With Arizona leading the way, four western DOTs are partnering to create a long-haul truck driver parking system by 2023, according to a report. The platform that Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas are building will track available truck parking at 37 public rest areas and 550 parking spaces in those states along I-10, the fourth longest interstate in the U.S.

Florida, with its massive population influx, has become a focal point for commercial transportation and the concerns—including the availability of truck parking—associated with the rapidly increasing freight movement there. One state trucking leader, Alix Miller, who is president and CEO of the Florida Trucking Association (FTA), sounded off to the overall industry angst about parking.

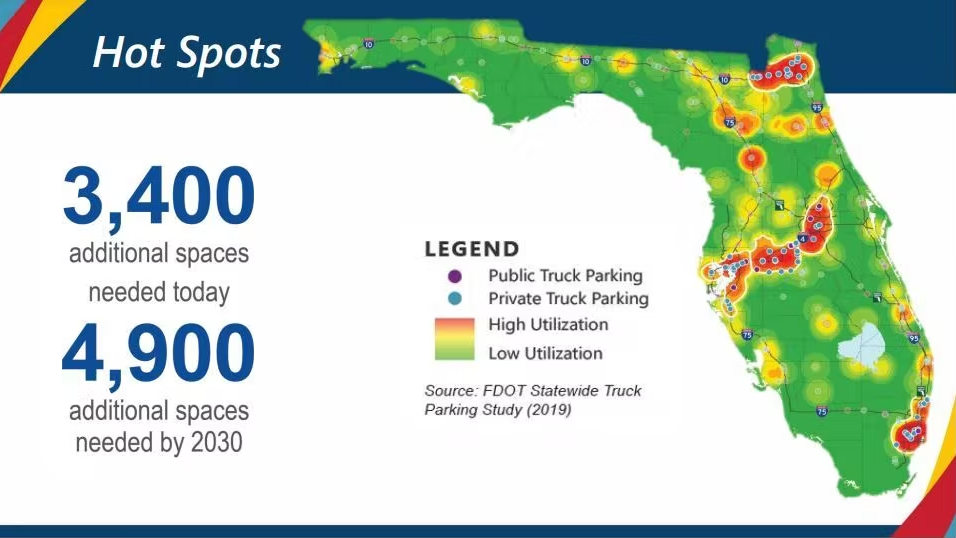

Miller emphasized the Sunshine State’s parking problem by citing statistics from a 2019 study and a later 2020 workshop by a frequent FTA working partner, the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT). The state needed 3,400 more spaces when the study was presented by FTA almost two years ago. And the clock is ticking—by 2030, Florida will need an additional 4,900 spots.

“We need to really address this—now,” Miller told FleetOwner.

Results from an annual study by the American Transportation Research Institute (ATRI) back up the unease that industry stakeholders nationwide are feeling about the truck parking issue.

The parking shortage ranks fifth on ATRI’s new list, revealed late last month at American Trucking Associations’ (ATA) Management Conference & Exhibition—only behind the driver shortage, driver retention, driver compensation, and lawsuit abuse reform. The same ATRI survey for 2020 ranked truck parking No. 3 on the list of industry concerns. In the new 2021 survey, parking challenges tied for the top concern along with pay among the survey respondents who identified themselves as professional drivers.

Truck parking remains “a very big concern,” ATRI’s president and COO Rebecca Brewster, emphasized at MCE, noting that parking has worsened during the pandemic.

Parking is a driver-centric problem

Chris Wagner, a professional truck driver for Freeport, Illinois-based Quality Transport, a small fleet that operates 20 power units, said he usually parks in public rest areas, where he spends his downtime in his sleeper. Wagner said he must watch the clock because the rest areas start to fill by about 4 or 5 p.m. After 6 or 7 p.m., finding a spot becomes more difficult. “Sometimes it is kinda tricky,” he said.

Wagner said that he’s knowledgeable about parking locations along his routes—he’s “old school”; he uses an atlas and a pocket truck stop book to guide him—but he conceded that a lot of truckers have to find unofficial spots or resort to the risky practice of parking along highway exit or entrance ramps.

During one run in Georgia, he said he had to park on a ramp, but law enforcement knocked on the door of his cab and ordered him to move. The few times he said he’s had to park on a ramp he’s used an entrance ramp, where traffic seems to move more slowly.

As far as searching for parking and his hours-of-service clock, Wagner said he’s cut it close. “I’ve pulled into spots with about two minutes on my clock,” he said, adding that other factors, such as slowdowns through road construction, have played a part in that, in addition to having to search for parking.

One idea that benefits drivers and seems to be gaining industry traction is that of asking shippers, especially when detention times draw out at many terminals, to provide onsite parking to drivers whose HOS clocks are running out.

Wagner said he takes advantage of these opportunities; a receiver at a frequent drop-off destination of his allows him to park long enough to restart his HOS clock.

Amanda Schuier, chief operating officer at Quality Transport, reported that she has called “a lot more shippers” to ask if drivers can sleep onsite. The fleet regularly juggles loads and drivers like Wagner to prevent them from running out of HOS on their way to search for parking or because of excess detention time, Schuier said.

“We would rather not deliver a load on time than risk an HOS violation,” noted Schuier, who travels personally and regularly to help drivers out of situations when they have run out of HOS. She tweeted on Oct. 18 that she was “playing Uber” for one driver, though his clock hadn’t run out searching for parking.

Trucker apps and technology

For another over-the-road driver, Jim Dowling, who drives for ATS Inc., figuring out the best time to shut down and begin looking for a place to park depends on his route for the day. When he’s on a dedicated route and knows where he’s going, finding a place to park isn’t as much of a headache. But not knowing where the next load is makes it harder to plan, Dowling told FleetOwner.

Dowling also said he feels there is a nationwide truck parking shortage “in a big way.”

“I will start looking for parking between two and three hours before I actually have to shut down, trying to get a feel for the area that I am in,” he said. “If I don’t have a good feel, I’ll just make the first one, and I might have to shut down two hours earlier than I really have to. But at the end of the day, the good news is that you can get up two hours earlier. The sooner you shut down, the sooner you can take your 10-hour break.”

Over the last two years, Dowling has turned to the Trucker Path app to find parking. He has found the app particularly useful in the highly congested Northeast.

Trucker Path, a mobile app for North American truckers, provides real-time parking availability and information from the more than 300,000 drivers who use the app daily. The app also includes more than 100,000 points of interest curated from the truck driver community. To date, some 1 million truck drivers utilize the app to find parking every month.

Through the app, any areas that offer truck parking have been geofenced, and whenever someone with the app from around the area offers a point of interest that has parking, there is a push notification that asks whether a lot, a little, or no parking is available.

“All of the data we get is from those geofences, and that crowd-sourced information really feeds the community,” explained Chris Oliver, chief business officer of Trucker Path. “The more we share it and make it available, the easier it is to find. The more drivers answer the questions, that data quality continues to get more reliable over time.”

“It’s that viral effect of you like it, you feed us, and we’ll give it back to you,” Oliver added.

In addition to parking, Trucker Path also features weigh-station status; real-time and crowdsourced driver insights for shipping and receiving facilities, showing the exact truck entrance, and information on overnight parking, check-in processes, wait times, and hours of operation; the ability for drivers to report road incidents caused by construction, accidents, police activity, and inspections so drivers can forecast potential transit delays; and weather alerts with map overlays and rerouting options.

“One of the things we are looking at is the weather by state and where travel is more difficult,” Oliver told FleetOwner.

“Safety is really the big thing,” he added. “Productivity and how much time it takes to find a parking spot is a huge issue. But there is Jason’s Law for a reason. We don’t want people parking on the side of the road where it’s dangerous.”

Regional players, some solutions for parking

Of course, the shortage of spots is not lost on regional transportation leaders such as Anne Strauss-Wieder, who is director of freight planning at the North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority (NJTPA).

She participates in an ongoing regional dialogue among officials in New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania about transportation challenges. Squarely among those is truck parking.

“We have to rebrand truck parking,” Strauss-Wieder said, adding that available stopping spots for professional truck drivers should be promoted as an “essential service.”

NJTPA operates an online map that identifies parking facilities throughout northern and central New Jersey that combines spaces available at private facilities, at travel plazas and truck stops, and on public lots and at rest stops. Each spot on the map identifies the number of spots available at that location and whether fuel, other amenities such as food, and overnight parking are available there.

What’s missing from the map, however, are real-time updates on how many spots are open or occupied. That is a technological hurdle that NJTPA has yet to overcome, Strauss-Wieder said. But the map might be one of the richer sources of parking information in the Northeast outside of Trucker Path, powerful smartphone apps on Apple’s App Store or Google Play put out by the travel plaza operators, or the network of electronic signs along roadways such as the ones erected two years ago in Ohio as part of an initiative uniting eight Midwestern states in the nation’s first regional truck parking Information system.

Strauss-Wieder said she works almost daily for a sustainable, long-term solution to the truck parking need, but the pandemic has shone a spotlight on the problem. She noted that Pennsylvania shut down its public truck parking early in the pandemic, and New Jersey almost closed its public spaces. But the other players in her region, New York and Connecticut, opted to keep theirs open.

A workshop last September that Strauss-Wieder moderated concluded that the truck parking problem became more acute in the pandemic’s early weeks when public parking facilities closed, and unofficial and unsafe parking was occurring on shoulders along Interstate 78 and close to New York City.

As Quality Transport’s Schuier pointed out, Strauss-Wieder mentioned that shippers and their terminals seem to be responding to the parking and other driver concerns, offering amenities such as food, temporary lodging, and even remote fueling, which was a measure especially in use during the pandemic.

Strauss-Wieder added that regional transportation leaders in the Northeast are discussing other ideas such as an Airbnb for professional truck drivers to find safe shelter—particularly when their ELD informs them their hours of service are running down or during weather emergencies.

Back in Florida, FTA leader Miller said the Interstate 4 “Disney” corridor and I-95 in many places from congested Jacksonville all the way down to Miami all lack enough truck parking, as surveys commissioned by FDOT also conclude.

She noted that the state had set aside rest stops that before could be accessed by the general public but had reserved them exclusively for truck drivers. She also cited a shortage in Florida of trucks stops and travel plazas—only one in every 30 or 40 miles of highway in the Sunshine State.

Truck stops remain THE parking resource

For truck stops and travel plazas—which still control the vast majority of parking spaces for the nation’s drivers—hindrances to building more plazas and opening up more spots can first be local community opposition and zoning restrictions, and then the sheer cost of construction if projects are cleared, according to a release from Tiffany Wlazlowski Neuman, who is VP of public affairs for NATSO, a Washington, D.C.-area trade association that represents travel plazas and truck stops.

“Truck parking is extraordinarily expensive to build and maintain. It can cost a private business $10,000 per year per space,” according to NATSO. “Yet the vast majority of truck parking is free to customers. Less than 2% of NATSO’s members charge for truck parking.”

In an interview with FleetOwner, Wlazlowski Neuman cited an idea that also seems to be gaining traction in the travel plaza industry—asking fleets to negotiate for truck parking in the same way they negotiate with truck stop operators for fuel contracts.

NATSO has been a significant stakeholder in solving the truck parking problem on the Federal Highway Administration’s National Truck Parking Coalition and works with the U.S. Department of Transportation and state and local governments to help address concerns around parking availability.

NATSO has recommended that state DOTs explore ways to lower the private sector’s costs, either through tax incentives or land acquisition and maintenance assistance. The trade association has tried to push the federal and state and local governments away from sponsoring competition to their business at interstate rest areas, which also host truck drivers and accommodate their parking needs. State rest areas that are commercialized “disincentivize private sector investments by granting states an unfair competitive advantage directly on the interstate right of way,” NATSO said.

Furthermore, Trucker Path data found that truck stop chains tend to be favored and filled up earlier more often than independent truck stops, rest areas, and other truck-friendly parking areas across the country. In addition, truck stops on the East Coast typically fill up earlier than those located out west, Trucker Path found.

Trucker Path recently broke down the fullest hours of the day for truck parking by region:

- In the Midwest region, most truck stop parking can be fully filled as early as 8 p.m., and chain truck stops tend to fill up earlier than independent truck stops and rest areas.

- In the Northeast region, most truck stop parking can be fully filled as early as 7 p.m., independent truck stops are usually filled up later than chain truck stops and rest areas at 8 p.m.

- In the Southeast region, chain truck stops get filled up the earliest by 7 p.m., rest areas get filled up the second earliest by 8 p.m., and independent truck stops get filled up the latest by around 9 p.m.

- In the Southwest region, chain truck stops get filled up the earliest by 8 p.m., independent truck stops get filled up the second earliest by 10 p.m., and rest areas get filled up the latest by 11 p.m.

- In the West region, chain truck stops get filled up the earliest by 10 p.m., and independent truck stops and rest areas both tend to get filled up around midnight.

When asked whether he feels there are enough nationwide truck parking places, Trucker Path’s Oliver said “probably,” but … “are there enough parking places where the trucks happen to be at the time when they need parking spaces? No way,” he stressed. “The need is very dispersed.

“Our industry is founded and based on being all over the place all the time,” Oliver added. “It’s very spread out, and as a result, it’s challenging. One of the big issues remains the amount of time spent finding a convenient and safe parking spot.”

Recent Posts

- Chime Expands Leadership Team with Addition of Real Estate Tech Innovator Stuart Sim

- Trucker Path Announces New Transportation Management System

- Chime Technologies Named Winner in HousingWire’s Tech100 Real Estate Awards for Third Consecutive Year

- Chime Invests $1M in Client Service Offerings and Triples Customer Success Team

- Chime Bolsters Leadership Team with Key Executive Hires; Increases Year over Year Headcount by Nearly 75%

Recent Comments

Recent Posts

Categories

- Chime (4)

- Trucker Path (3)